…As we climbed higher, the way got narrower and narrower, and the walls steeper and rockier. In the narrow passes there was moisture in the soil, and plenty of grass. It was a perfect wallaby habitat. As we came around a rocky outcrop, into the head of the canyon, we stopped dead in our tracks. The whole canyon was just full of goats. Feral goats. It was like a scene from a weird Hitchcock movie…

The road west, from Whyalla to Iron Knob, is straight and lonely. As the day wears on heat haze shimmers on the tarmac. My eyes ache from the glare. I pull my hat low over my eyes.

Four or five vehicles have gone past in the last hour, mostly trucks which show no sign of slowing down. The big trucking companies ban their drivers from picking up hitchhikers, and in the last few years they have started putting little cameras in the trucks to spy on their drivers. The only truckies who stop for hitchhikers now are men who own their own rigs, and they are few and far between in outback South Australia.

(Top photo: yep, they’re wallabies alright, but no yellow feet.)

I plonk myself on the ground and rest for a while. I have a drink. I still have almost a litre of water.

It’s almost eleven o’clock. I should find some shade under a tree and wait until it starts to cool down. There’s just one problem with this idea. No trees in sight. The plain is dusty and barren in every direction. I curse my stupidity for getting dropped off here. I should have waited for a longer ride in town.

A big white ute appears on the horizon. I squint into the glare. Is the ute slowing down for the intersection? Yes. He’s got his indicator on now. he’s going to turn down this road. I jump to my feet. I feel dizzy. Thumb out. The ute makes the turn. It’s a four seater, and the tray is loaded with camping gear. The ute slows and pulls up. Relief. I jog to the driver’s window. The bloke behind the wheel has a sunburned nose, a broad smile, and a long grey beard.

Where you going, mate? he asks me. We can take you to Ceduna with us tomorrow if you like. Tonight we’re going to camp in the Gawler Ranges.

(This is one of the hottest, lonliest places I’ve ever stuck my thumb out.)

Graham and Lindy are headed to Ceduna to start new jobs. Graham is going to be the regional bushfire prevention officer, and Lindy is going to take charge of weed management. They are both scientists, but I can see it’s a long time since either of them wore a white coat.

Pretty much everything we own is in the back of the ute, Graham says.

We don’t have any kids, so we can move around a lot, says Lindy.

The two exchange a glance and Graham squeezes Lindy’s hand.

As long as we can live in the bush, and make enough money to eat, we’re happy, Graham adds.

At Wudinna, a highway town dominated by four massive silos, Graham steers the ute onto a rutted gravel road. We head north into the mallee scrub. The vegetation out here is mostly salt bush and yellowed grass. Lindy tells me that grasses are a big weed problem in the Australian outback now. Over recent decades hundreds of exotic grass species have been introduced. The grasses are meant to be arid climate stock feed, but their tenacity has made them a threat to the ecosystem as well.

Seventy kilometers into the national park, Graham pulls up in a dusty camp ground. The only thing that distinguishes it from the surrounding plains is a rusty steel fire pit. The sandy soil is ochre red, and scurrying ants swarm around, expectantly waiting for us to drop crumbs.

There is a creek bed running past the camp ground but it is as dry as everywhere else. The only visible life is the paper dry grasses, swaying in the breeze like a yellow ocean.

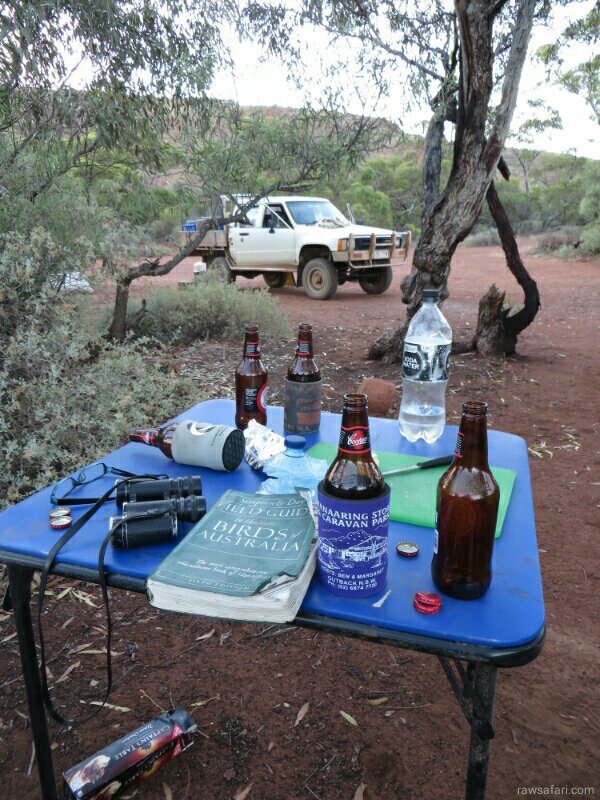

I pitch my bivouac, and Lindy throws their mattress on the ground. Graham gets out a small folding table, and we sit on a log and have a beer. Lindy digs in the tucker box and finds a cheese and some crackers. We watch the sun dip on the horizon, drink our beers and chat about biodiversity.

A lot of the plants you see on these plains now are like a ecological disease, Lindy says. They go crazy, dropping seeds and spreading everywhere, and pretty soon all the native plants are gone. It’s the same with feral animals. A couple of years ago we went to a forest in Queensland to find a rare wallaby. We heard from the locals that the best place to spot them was in a gorge in the hill country. We headed up there. It took about three hours to walk up the valley. As we climbed higher, the way got narrower and narrower, and the walls steeper and rockier. In the narrow passes there was moisture in the soil, and plenty of grasses. It was a perfect wallaby habitat. As we came around a rocky outcrop, into the head of the canyon, we stopped dead in our tracks. The whole canyon was just full of goats. Feral goats. It was like a scene from a weird Hitchcock movie. They were all over the place, hundreds and hundreds of them. All up the rocky walls of the gorge, in every shady corner. And in the middle of this massive herd of goats, were a handful of the rare wallabies we had come to see. They looked pitifully outnumbered. It was like a literal demonstration of what happens when an exotic species finds a niche. They just breed like mad, and pretty soon they force the native species out of its home.

(Our campsite in the Gawler Ranges National Park.)

Lindy lights a fire and we sizzle some sausages. The moon comes up, and the grass plains become an eerily beautiful blue, more like a calm sea than ever.

When I turn in for the night I seal up my insect net tightly. the ants have settled down a little bit, but some of them are absurdly big, and I don’t fancy sharing my sleeping bag with them.

We are up at dawn the following morning, throw the gear on the ute, chug some instant coffee and head out.

There’s a spot in the national park known as ‘The Organ Pipes’. Graham and Lindy are hoping to find another rare wallaby in the area.

We are a bit obsessed with wallabies, Lindy admits. They are amazing animals. Very highly adapted to their niche.

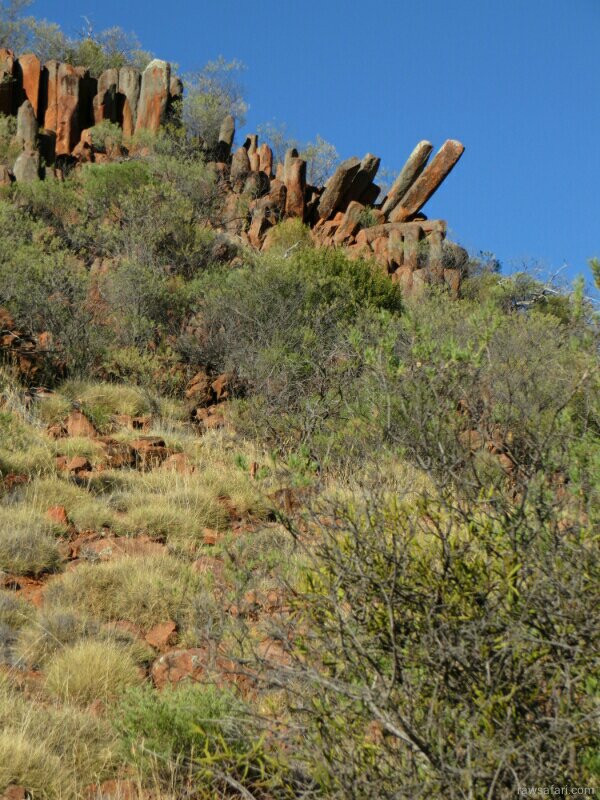

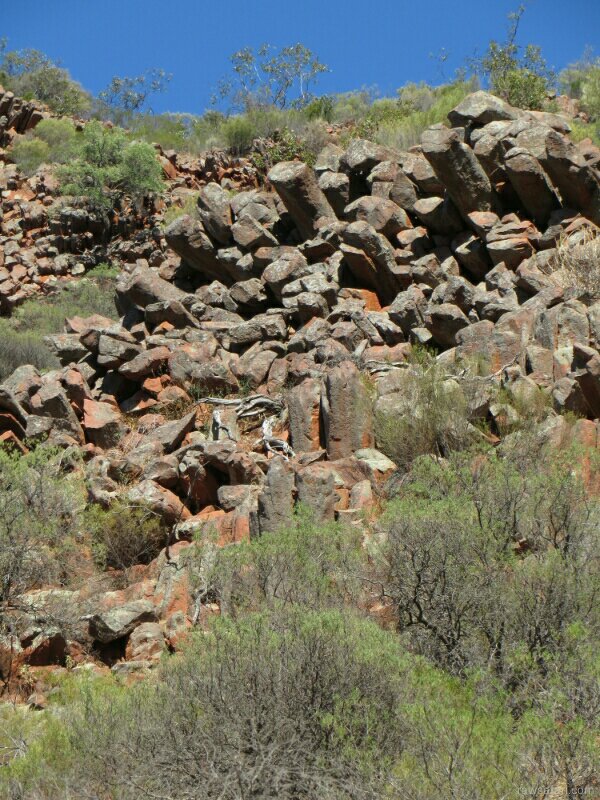

We hike into the hills and follow the dry creek bed up the steep, rocky slopes. The jagged stones along the hillsides are indeed slightly reminiscent of organ pipes, or stone columns. The mild dizziness caused by the heat probably helped the European explorers who named them see the similarity. There is no water in the stony creek, but the high water mark, from previous wet seasons, is visible on the parched rocks.

Graham spots a wallaby and gets excited, but after looking through his binoculars, his excitement subsides. It is not the rare specimen they are looking for.

The Yellow Footed Rock Wallaby, Graham informs me, is a very distinctive animal, with orange tinge to its fur, and a tiger-striped tail. If he sees one, he will know.

As we climb higher I see plenty of stripy lizards, but no yellow footed wallabies. We get to the top of the hill, and Graham is forced to admit defeat.

I hope there are still a few here, Lindy says sadly. It’s been a very harsh couple of years.

Graham squeezes her shoulder reassuringly.

Ah well, they’re probably just hiding out from the heat, he says gently.

The rocky hills are beautiful, and we take a lot of landscape photos. Just as we are preparing to head back down to the camp site, Graham gasps and snatches up his binoculars.

Look! he hisses, pointing to a small silhouette, perched on a rocky crag on the summit of the dry waterfall. That’s it! Graham whispers excitedly. That’s it! I can see the striped tail!

Lindy wrestles the binoculars out of his hands and peers up the rise.

Oh my god, she gasps. Yes!

The scientists embrace each other like proud parents whose kid just scored a goal.

Lindy hands me the bino’s.

See it? she urges me.

I stare at the silhouette on the ridge, and sure enough I can just make out the stylish stripes on the long, agile tail.

I get out my camera, but by the time the lens is open, the wallaby has turned lazily and hopped out of view over the horizon line.

Lindy sighs deeply and contentedly.

He looked in good shape, she says happily. They must be doing alright here.

Graham grins.

Yeah, he was a fat little bugger, he agrees.

We head back toward the camp site. Graham points out some places in the creek bed where the soil is a bit darker.

If you dig down in spots like that you’ll find fresh water, he tells me. Even creeks that look dry often have underground flows. You just have to know where to look.

The scientists hold hands as we walk down the hill and call out the Latin names of plants to each other.

(There are some long, straight roads in this part of the world. This one goes north from Wudinna.)

(The Organ Pipes – so named by a delirious European explorer I’m guessing.)

(Graham and Lindy hiking into the hills to find their wallaby.)

(Somewhere out there is a small, perfectly camouflaged marsupial.)

(A Blue Tongue skink – Latin name: Tiliqua Nigrolutea.)

(Cheese and crackers. Very civilised.)

(Graham teaching me about feral goats.)

(There was water here some time.)

>> More stories about Australia.

>> Follow Raw Safari on Google+.