…My left knee jams under the accelerator grip, and the next thing I know, I’ve lost power, lost my balance and I’m toppling, slowly and gracelessly toward the ground. A group of monks are laughing at me uproariously. I pick myself up with Buddhist humility, and ride slowly and carefully out the temple gate…

Flashback: 2007.

Chiang Mai. Northern Thailand’s venerable walled city. A seething metropolis of tangled streets, narrow alleyways, temples, street markets, retail super-centres and seedy go-go bars.

I hitchhike into town with an off duty bus driver. His small son and I are the only passengers. I keep the kid entertained telling him jokes in English, and having gun duels with water pistols.

I get into Chiang Mai late at night and check into a humid hostel room. I fall into bed. I’m exhausted. Hitching in Thailand can be very tiring. It’s easy to get rides, but the walking is killer. The intense heat and humidity drain the energy out of me.

I have a late breakfast at a street stand. It’s an especially hot morning, even by Thai standards. I set out to see the city. Four blocks later I’m sweating like a pig on a treadmill. I slump into a chair outside a cafe and order a long drink. While I’m sipping my coconut juice, I notice the scooter hire place across the street.

So far I’ve resisted the temptation to ride in Asia. I’ve heard so many stories about accidents, broken limbs, corrupt cops extracting bribes, and scammy hire companies. But it’s so hot. So fucking hot. I feel like I can’t face another day of walking.

I hire a fully automatic scooter. I’ve never ridden before, so I need to start nice and easy. I get the hang of the simple controls very quickly. Thai traffic; that’s another story. There don’t seem to be any road rules. There are lane markings, but nobody stays in their lanes. There are millions of other scooters on the road. They swarm like wasps around me, and the cars and trucks butt into any small gap that appears in the swarm.

Once I get past the initial terror, I gain confidence quickly. Pretty soon I’m zooming happily through the city and suburbs, seeing the sights, and dodging potholes and lories.

I visit one of the city’s biggest monasteries. It’s like a small village within the city. The monks are serious looking people in traditional orange robes, who seem indifferent to the tourists like me, sightseeing in their domain. Indifferent… until I fall off my bike. The accident is ridiculous. The scooter is very small. I am very tall. My knees are barely half an inch under the handlebars. Distracted by the monastic architecture, I forget to move my knees as I lean into a corner. My left knee jams under the accelerator grip, and the next thing I know, I’ve lost power, lost my balance and I’m toppling, slowly and gracelessly toward the ground. I’m not hurt, but I’m really embarrassed. A group of monks who, moments ago, were parading serenely with holy detachment in their eyes, are now laughing at me uproariously. I pick myself up with Buddhist humility, and ride slowly and carefully out the temple gate.

I spend three days seeing Chiang Mai. I return the scooter to the hire place. It’s time to head out of town. I’ve heard good things about Thailand’s far north. Mountains. Rivers. Remote villages. I need a bigger bike.

Tony’s Big Bikes has what I need. I rent a Suzuki 400 cruiser for the equivalent of fourteen dollars a day, Australian. The bike is much bigger and more comfortable than the little scooter. It looks a lot cooler too. Chrome. Leather. Red paint. A rumbling, snarling exhaust. There’s just a few problems. A clutch. I have never ridden a bike with a clutch. Pedals. Ditto. There are five speeds. The bike weighs twice as much as I do.

Tony gives me the key and a helmet and I swing myself into the saddle. I fiddle with the helmet strap to buy some time while Tony walks back inside the office. I have no idea how to ride this thing. I grip the handlebars and hesitantly turn the key. The engine growls to life. By trial and error I figure out which peddle changes the gears, and which is the brake. I squeeze the clutch, and kick the bike in gear. With a tyre squealing lurch, I let out the clutch. The bike barges into the street and swerves into the traffic. I hang on, white knuckled. The bike roars and trembles, and I realise I need to change gears. Second. Third. Traffic light. I hit the brakes. The engine stalls. I’m riding a real motorbike. And I’ve survived the first two minutes. Result.

I spend the next two hours riding around the city in circles. Pretty soon I can change gears smoothly, and draw to a stop without stalling. I manage not to collide with the other tightly packed road users. I’m ready for the highway.

The roads of northern Thailand are a biker’s wet dream. Long, curling hill climbs and descents, magnificent views. Every ten or fifteen kilometres there is a road-side stand selling fruit, barbecue snacks and beer.

There’s one old guy with a sign saying he is selling fresh fruit for ten baht a bucket. I stop and ask him to give me half bucket. He jumps up, climbs the tree behind him, and fills a bucket with fruit straight off the branches. He must be seventy years old by the look of his leathery face, but he climbs like a ten year old.

There is only one down side to riding in Thailand; the trucks. Thai truckies are a pretty relaxed lot. They’re never in a hurry, they smoke and drink behind the wheel, and they aren’t too fussed about which side of the road they drive on.

I’m really starting to get into cornering. I’ve realised why people get hooked on motorbikes. It’s all about the curves. Carving. Rolling the bike into steeper and steeper corners. Judging the exact right moment to gear down into the turn, and then opening up the throttle and feeling the surge of power as the bike drags itself upright and roars into the straight.

As I lean into a tight bend I am suddenly confronted by the blunt end of a lorry. The truck is my lane. Not just a little bit over the line, actually in my lane. On a hairpin bend. On the side of a mountain. Luckily for me, I’ve worked out enough about riding already to keep to the inside of the curves. I jam my foot on the brake – throw my weight into the corner. The bike shaves into the shoulder, and I feel the back wheel shudder and skid on gravel, but I graze past the side of the truck, and get the bike under control and I survive. And the trucky has the nerve to blast his air horn at me. As soon as I get the handlebars straight I shoot my arm in the air and give the trucky a furious one finger salute over my shoulder. It’s a waste of time. The bend is so sharp he’s already out of sight. The ferocity of my flip-off sends the bike into another wobbling fit. With hands like claws, I grab the bars, throttle down and pull to the side of the road.

It takes me about twenty minutes to stop shaking. Falling over in front of the monks was an embarrassment, but this experience was terrifying. This sort of thing must be what makes bikey gangs so angry and aggressive. I get my shit together, jam my head back in my helmet and take a deep breath. I got to get back on the bike before I lose my nerve.

I turn the key, and roll back onto the road. From now on, I’ll take it slow. Safety first. I’m not in a hurry. I’ll ride to survive.

Five minutes later, barrelling down a steep straight, and overtaking trucks like they are standing still, my fear is forgotten in the rush of bike adrenalin. In a moment of clarity, I realise; I’m addicted already. Riding a bike makes heroin look like a safe hobby. I do make one concession to caution though. Every time I approach a tight bend I squeeze the horn button and hold it in until I’m back on the straight. Take that truckers.

Bikes are great transport. Fun to ride. Easy to park. Great on fuel. Buying petrol is easy in Thailand too, because there are petrol stations everywhere. All you need in Thailand to set up a petrol station is a simple wooden rack and fifteen or twenty empty glass bottles. When the bike runs low on gas, I pull up at one of these side-of-the-road racks, and the enterprising proprieter decants fuel into my tank from one of the glass bottles. Very convenient. One coke bottle keeps the bike running for more than a hundred kilometres. You need cash though. These small filling stations do not accept Amex.

Riding a ‘big bike’ (as anything over 125 cc is called in Thailand) gets me a lot of prestige. When I approach police check points, the cops swing the boom gate open straight away. One beaming cop actually gives me a smart salute as I ride past, which I naturally return with due seriousness.

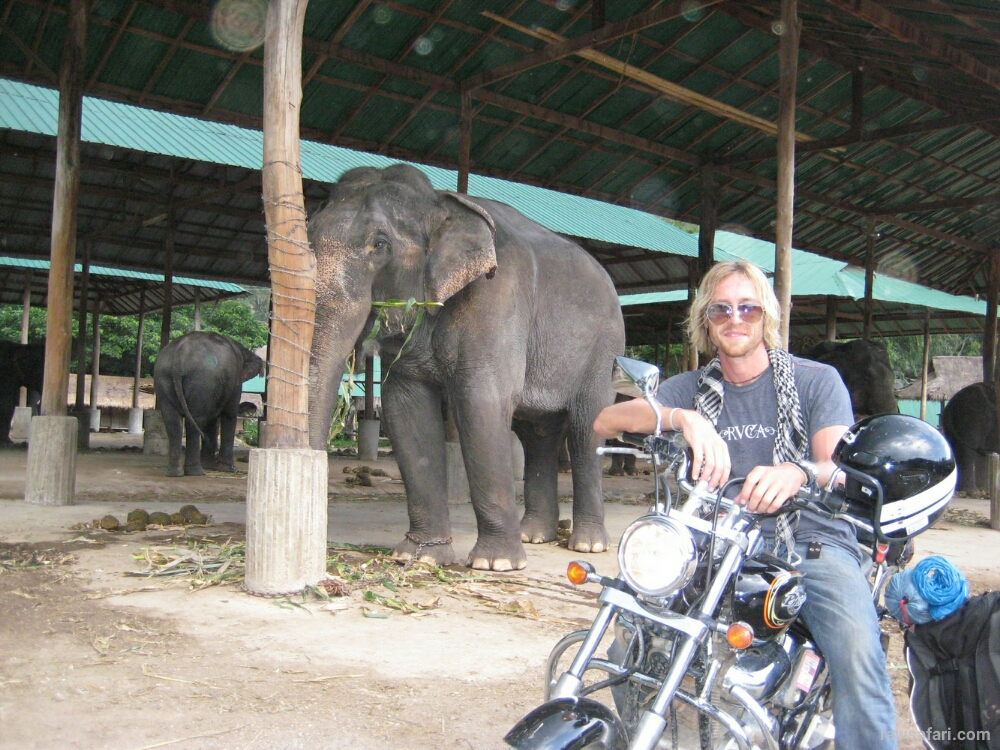

(Above: Thailand’s two most popular forms of transport.)

As I get further north, Thailand’s topography gets steeper, and the culture gets increasingly rural. In this part of the country, people ride donkeys, and carry their tools on handcarts rather than scooters. The country women wear traditional outfits; colourful dresses and blouses embellished with bells, beads and embroidery. I pass elephant farms, where the giant animals are bred for use in forestry and construction. When I get caught in a downpour one afternoon I take shelter in a bamboo shed, where three elephants are resting, their ankles chained to massive stakes. It’s the closest I’ve ever been to an elephant outside a zoo. They are smelly, but very placid.

I keep passing rough dirt tracks leading up into the farmland on the hillsides. I am curious. I turn onto one and carefully climb a steep, rutted track. The cruiser isn’t built for rough surfaces, so I take it slow, but it is tricky riding.

I pull up at a part of the track which is completely boggy. There is a small stream running out of the jungle to the right of the track, and the track is more like a muddy creek bed than a road. I walk over to the quagmire, and check the depth with a stick. The mud is only about four inches deep, but it is sticky, and smells like shit.

I get back on the bike. I remember reading somewhere that keeping a bike steady is all about centre of gravity. It’s important to keep your legs tucked in, and hug the saddle with your knees.

I put the bike in low gear, and start across the bog. I immediately find myself railroaded into a deep furrow. The front wheel sinks deeper and deeper. When I am halfway across, the rear wheel suddenly lurches to the left, as if it has slipped into another rut. I try to straighten the bike up, riding the clutch and revving the engine, but I’ve lost it. The front wheel is so deep in the mud that I can’t really steer, and as the back tyre starts to spin, and slip sideways I can feel myself toppling over. Keep your knees tucked in, keep your knees tucked in, keep your… The bike topples over, with me under it.

I’m familiar with the sensation of falling off a bike now, but the wet slap, and smelly embrace of the mud is a new and exciting addition to the experience. I lie there for a moment, slightly shocked, with the damn thing pinning my leg down in the mud. I’m not hurt. Falling in mud is, at least, not injurious. I pull my left leg out from under, and stagger to my feet. My jeans, and the left side of my torso are completely brown, and dripping with slop. There are plenty of donkees on these hill roads, so it’s not a giant leap to figure out what gives the mud it’s ripe flavour. I try to scrape some of the mud off myself, but realise how pointless this is, since I have to get the bike out of the bog. I wade into the bog and drag the bike upright. The mud makes a slurping sound as it lets go of it. Slipping and stumbling, I push the bike the rest of the way across the mire, and take stock. I am dirty. And wet. My bag is wet. The bike is covered in mud. I turn the key, and the bike starts, so at least that’s OK.

(Above: In rural Thailand they seem to spend more money on building Buddhas, than building roads.)

I look ahead, and see a small village further along the road. I ride into town looking like I just did some sort of off-road challenge, like the Camel Trophy. The village is only about a dozen small bamboo houses. There is one tiny shop, selling rice and coke bottles of petrol. There is a pig pen. That’s about it. I stop outside the small shop. The shopkeeper stares at me and laughs.

‘It looks like you need a bath, sir’ he tells me.

I nod and grin sheepishly.

‘There is no bath here’ he tells me, ‘but I have a hose.’

He drags a length of rubber hose out from under a makeshift water tank.

‘Stand here’ he instructs me.

I stand in the road, and the shopkeeper sprays me and the bike with the hose.

When I am a bit less muddy, he shuts off the water.

‘Thank you’ I tell him. ‘Where can I get something to eat here?’

‘Hmmm. No restaurant in this town, sir. I have some food in the shop.’

He gestures for me to come into the tiny store. I step inside, dripping. There is not much of a range of products. There are five, ten, and twenty kilo bags of rice. There are live chickens in a cage. There are raw eggs. There is a dozen or so bags of deep fried pork rinds. I select two bags of pork rinds, pay the shop keeper, and sit down on the bench in front of the shop.

‘Where are you travelling to?’ the shopkeeper asks me.

‘I’m going to Pai’ I answer, through a mouthful of pork rinds.

‘Oh yes, Pai. Many tourists like to go to Pai. It is a party town. Lots of music and dancing.’

‘You speak very good English’ I tell him.

‘Yes. I am a school teacher’ he tells me.

‘Oh? Where do you teach?’

‘Right here’ he tells me. ‘I teach all the children in this village. I have twenty-eight students this term. Many people do not want their children to go to school, but work in the farms instead. That is bad. Education is very important.’

I nod my agreement. A pig runs past, chased by four small, shirtless, boys. When they see me, they lose interest in the pig, and stare, open mouthed at the giant freak, sitting outside the shop, dripping wet, eating pork rinds.

The shop keeper / teacher says something to the boys, and they run off.

‘It’s OK’ I tell him, ‘I’m used to being stared at here.’

‘That’s good’ he says. ‘I told them to bring everyone else. This is a good opportunity for them to practice their English.’

By the time I have started the second bag of pork rinds, I am surrounded by what looks like every kid in the village. Their teacher tries to encourage them to speak English with me, and a few of them say ‘hello’, and ‘good morning, sir’, but they are much more interested in the bike.

As well as all the kids, a guy in a uniform shows up. At first I think he is a police officer, but then I notice his gun is a plastic toy. He stands off to one side, studying me with crossed eyes and a shy smile.

The teacher notices me looking at the guy with the toy gun.

‘He is my assistant’ he tells me. ‘He is our town sheriff, also’ he says, and pats the uniformed guy’s shoulder, indulgently.

I take a few of the kids for a ride up and down the street, and then realise my mistake. Now every kid wants a go. I spend an hour or so giving the kids joy rides, then I make my excuses and prepare to depart.

There is a narrow track leading uphill from the northern end of the village. I ride up the hill, and the track gets narrower, and narrower, until finally it is just a single dusty footpath, scattered with animal dung. I find a small clearing to the side of the track and pitch my tent.

As the sun goes down, the view from the hillside is beautiful. The mountains in the distance turn crimson, then purple, and finally, as night falls, a deep blue.

I sleep soundly, if rather sweatily.

In the morning I am woken by the sound of cattle bells. I stick my head out and find a herd of cows trudging past my tent.

I pack up the tent and get on the bike. The trail leading up the hill is much too narrow and boggy to ride on, especially after the cattle have gone by. I point the bike downhill, and ride back the way I came the previous evening.

I stop off at the teacher’s shop for some breakfast. The teacher isn’t there, but the cross eyed sheriff with the plastic gun sells me a bag of freshly fried pork rinds.

>> Share this on Facebook!

>> More stories about my misadventures in Thailand.

>> Check out the Raw Safari Top 9 Low-Budget Adventure Tips!