While we weave, Bianca tells us a story… “Mum has always been an activist. She has always been a proud and vocal Aboriginal woman, but when I was in my teens I was ashamed of who I was. I grew up in a context that was profoundly racist. At school I was regularly abused and made to feel like I was an outsider. People called me names. They used language they new would humiliate me. Words like coon, boong, Abo’, nigger. I was even spat on and physically threatened.

Next Stop.

At the end of the gathering at Springbrook, I ask around for a lift. TheOldOne (that’s his name) is a bloke with long bony legs, and a spherical hedge of greying blonde hair. He is loading his tent, and his kids into a van.

“I can squeeze you in” TheOldOne tells me.

I peer into the van dubiously. “You sure about that? Looks pretty loaded.”

“Of course. Always room for one more. We can get you as far as Maleny anyway. Where do you want to go?”

“I’m not sure really…”

“Why don’t you go to Mimburi for a couple of days? You been there before?”

“No… What’s at Mimburi?”

“It’s a really beautiful farm. The lady who runs the place, Beverly, and her family, they’ve made it a community hub for the local indig’. They host festivals, and do traditional cultural workshops and stuff. Good people.”

(Top photo: Bianca showing how to do traditional grass cord weaving.)

I clamber out of TheOldOne’s van in Maleny. He writes some sketchy directions on a scrap of paper for me.

I haven’t spent much time in the Aboriginal community. I meet indigenous Australians all the time when I’m hitchhiking, though. Aboriginal people understand nomadic life I guess, and they are happy to help out a traveller, regardless of skin colour. I meet indig’ at gatherings like Confest and Rainbow too, but they are always a tiny minority, just as they are a tiny minority in the broader Australian population.

Visiting an Aboriginal community as a white Australian, I have no idea what to expect, but I am confident that if I observe the universal rules of respectful conduct, I will be made welcome.

My Skin.

When I was a kid, I lived in a regional town called Wagga Wagga.

I am white. My parents are both Caucasians. My Dad is broadly British (a bit of Scot and English), and my Mum’s parents were from Poland. Ethnicity was never very important to me growing up. I was a white Australian, so it was never a topic of discussion.

In 1988, Australia celebrated it’s Bicentenary. The Bicentenary was a strange thing, all round. It was actually much less than one hundred years since federation, and before that Australia, as a single community, didn’t officially exist. The event that the bicentenary was supposed to commemorate was the arrival of the “First Fleet”. These were the infamous convict boats, that brought the first civilian Europeans to the continent, in chains. In 1788 the boats landed. The sick and malnourished white people staggered ashore, shackled and wretched, and a man in a ridiculous hat declared that this was now the colony of New South Wales, a British posession.

The chained convicts were set to work building houses and roads. Trees were felled, land cleared and farms established.

There was, of course, one small glitch. The continent that the white people were colonising was already occupied by brown people. Nobody let that bother them too much, though. As long as the brown people stayed out of their way, the white people just ignored them, and if the brown people resisted the encroachment, the white people just shot them, as if they were pesky wild animals.

None of this story was given much attention during the heady celebrations in 1988. The bicentenary coincided with a time of prosperity for white Australians. We had barbeques, pool parties, piss-ups and parades.

On Australia Day, January 26th, everyone was terribly proud to be Australian. The Australians with brown skin looked on with disbelief as the nation celebrated the two hundredth anniversary of an invasion.

In the 1980s, my parents were involved in all kinds of community activism. I was raised to think like a radical. My parents wanted to help other white Australians understand the bicentennial controversy. My dad managed the city library. He and my mum organised a series of lectures in the library meeting room. The speakers were elders of the Aboriginal community. They spoke about their experience of being indigenous Australians. They talked about their parents and grandparents, who grew up in an Australia where they were denied voting rights because they were Aboriginal. I was fifteen years old. I went to all the lectures. I realised that if you were Aboriginal, the bicentenary was not a thing to celebrate. If you were Aboriginal, 1788 was the commencement of a genocide. If you were an Aboriginal Australian, your family had been disposessed of their land, your culture had been systematically eradicated, your forebears had been made slaves, your grandmothers had been raped, and your grandfathers murdered.

In 1988, Australia’s bicentennary year, I became concious of my caucasian ethnicity. My parents were WW2 migrants. My family was not responsible for the Australian genocide, but my culture was.

As I have hitchhiked around Australia, these past years, I have met many white Australians who were openly racist. I have heard white people declare that the colonists should have ‘finished the job’ and wiped out the ‘Abo’s’ completely.

I have never encountered racism from an indigenous Australian. Despite the cruelty and indifference of white culture toward Aboriginal people, they still stop for me when I hitchhike, offer me a couch to sleep on, and share their cigarettes with me.

If there is a race problem in Australia, it is not being caused by brown people.

(Below: in 1988 I wore a pin like this on my hat. Nobody in the little town I grew up in knew what the fuck it meant, but it was a conversation starter.)

Jam Night.

I arrive at Mimburi in the late afternoon. I meet Beverly down at the shed. She and her son, Alex, are setting up for the Saturday Jam Night. I can’t believe my luck. Once a month they host a music night, and I just happened to arrive on the right day. Beverly and Alex immediately make me feel welcome. Beverly is a boisterous, smiling woman, with big teeth and eyes that constantly sparkle with good humor.

Alex gives me a quick tour. He shows me a picturesque river at the bottom of a sloping field. I have a swim and feel hugely refreshed.

(Above: the river at Mimburi.)

I pitch my tent in the horse paddock behind the shed, and join the party. Beverly gives me a coffee, and I slump gratefully into a big couch beside the fire.

There is a girl sitting in an armchair beside the couch. She is strikingly beautiful with high cheekbones, a petite nose, and intense brown eyes. There is an asymetrical curl to her upper lip, which gives her a look of perpetual mild amusement. She looks up, and catches me staring at her.

“So, who are you?” she asks me, simply.

“I’m Manny” I say, and smile.

“I’m Bianca. I’m Beverly’s daughter. You play music, Manny?” she asks.

“Yes, I do. I heard there’s going to be a jam session tonight.”

“Yeah, should be a good one. There’s lots of people coming to play tonight. Stick around, you’ll have fun.”

“Thank you. I will.”

Bianca nods, and smiles gently, revealing a pale scar on her freckled upper lip. She rises, and goes to talk with a group of other young women in the kitchen area.

Alex starts playing blues on a battered guitar. I join in for a couple of songs.

As the twilight deepens, more and more people arrive, in utes, and battered old 4×4’s. Everyone has a guitar case, or a platter of food. Pretty soon the party is in full swing. Alex sets up a P.A. and microphones. The Jam gets going for real. I hessitate to get up on stage, but Beverly urges everyone to join in. She is a born MC. She takes the mic between sets, telling stories, improvising poetry, and encouraging the less confident musicians, like myself.

The night is incredibly good fun, and the atmosphere is like a big family reunion. There are quite a few Rainbow people there. Mimburi hosted a Rainbow Gathering a couple of weeks earlier, and there are still a bunch of tents and a tipi pitched down by the river.

The music covers many genres: blues, rock, cool jazz and country, and everyone has a go at everything. We are all there to share music, and have fun.

Late in the night, after the P.A. is powered down, a few of us sit around in the fading fire light and talk about big stuff. Politics, community, spirituality.

I learn from Alex and Bianca that the government is trying to push them off the land. Beverly leases Mimburi, and the government has decided they want to sell it. They have given Beverly an ultimatum: come up with the purchase price, or face eviction. Bianca tells me all this matter-of-factly, but the ugly irony is not lost on any of us. This land was taken from Aboriginal people a hundred and fifty years ago, and now the Australian Government wants to push them off it again.

Beverly, Alex and Bianca are co-ordinating a campaign to keep their land. These people will not lie down.

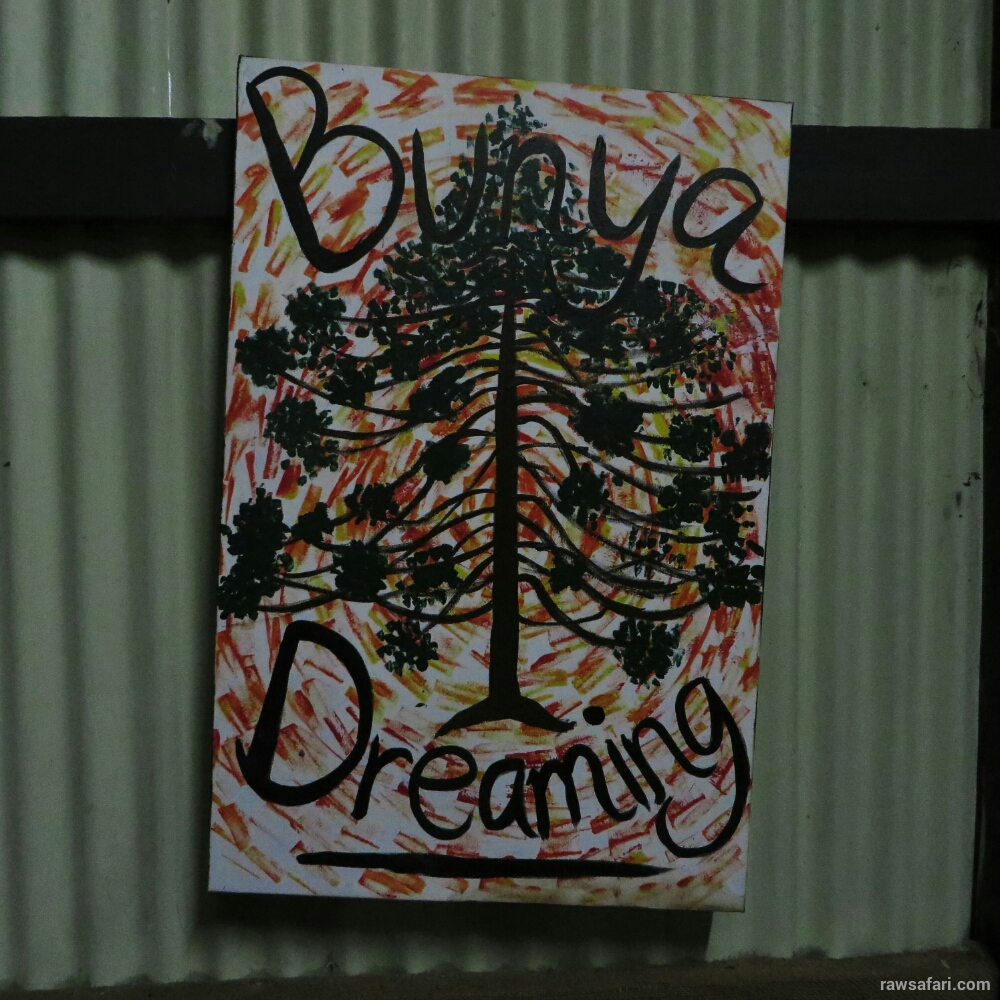

“Buying this place isn’t enough” Bianca says. “For me, the goal is sovereignty. We want recognition of our right to be here. We are descendants of the indigenous people from whom this land was stolen, and I won’t rest until we have independent control of our own destiny here. This place was a traditional gathering site. Every year, when the Banya trees fruited, the tribes would come here to feast and have a conference. There were sacred rituals, treaty talks and marriages here. We want that tradition of the Banya Dreaming to be reborn. That is why we have opened our land and our hearts to other people, as well. We want this to be a gathering place for all the tribes, white, black, whatever, to come together, and celebrate co-operation and peace.

I’m a very contemporary Australian woman. I have an education worth a couple of hundred thousand dollars. But I am also a black woman, and I want dignity and sovereignty for my people.”

Jokes.

Flashback: 2012.

I’m camping in the forest near Majors Creek, with a bunch of rowdy red-necks. Everyone drives a big 4×4 and drinks beer as if they own shares in a brewery.

Sitting around the camp fire late one night, someone starts telling racist jokes.

“What do you call an Aborigine in a suit..? The defendant.”

“How do you tell the difference between a dead kangaroo and a dead Abo’ on the road..? There’s skid marks in front of the ‘roo.”

“How do you stop an Abo’ from drowning..? Take your foot off his head.”

Everyone round the fire is laughing except me. My wife is brown skinned. She is Indonesian. My objection to racist jokes is personal. My wife isn’t here with me, and I’m pretty sure if she was, they wouldn’t be saying this sort of shit. But they think it’s just us white men sitting around having a beer, so nigger bashing is OK.

“What do you call fifty drowning Abo’s..? A bloody good start!”

There is a lot of drunken laughter.

“They did the job right in Tasmania” one old bloke says. “Pushed the lot of ’em into the sea. No boongs left in Tassie’!”

One of these guys, laughing, is a friend of mine; Geoff. I know I have to say something. I need Geoff and the others to know that their ignorance and insensitivity is hurtful.

When there is a pause, I speak loudly and clearly:

“You know, in Indonesia, the natives outnumbered the white people thousands to one. When the brown people got sick of the white people pushing them around, they picked up guns, and forced the whiteys out of their country. We white people are very lucky, here in Australia, that there weren’t many Aborigines, or things might have been very different here.”

There is a long silence. The fire crackles. Someone clears his throat and spits. My friend Geoff casts a quick glance in my direction and chuckles nervously. The conversation topic changes to football.

The following morning, Geoff makes a delicious hot breakfast for me and insists that I have extra helpings of bacon. I accept the apology. Geoff knows my wife, Nia. He must feel bad about being so rude the previous night. I feel like he has probably never even thought about his racist attitudes. He comes from a small town. He has probably grown up hearing his father, and his uncles, and his friends spouting bullshit, and he has just repeated the same crap without ever stopping to think about what he is saying. Until today.

Weaving.

The day after the big jam night, we all sleep late. I crawl out of my tent, bleary eyed, to find a horse staring me in the face. I get such a shock I stumble backwards, and nearly flatten my tent. The horse realises I am not in posession of anything tasty, and ambles off. I head for the shed to make a pot of coffee.

Alex is stirring the ashes of the fire back to life.

“Bianca’s coming down soon. She’s gonna do a weaving workshop.”

“Oh! Cool. Can I join in?”

“Definitely, mate. Make us a cup of coffee and I’ll tell you all about it.”

Half a dozen of us are sitting around the fire when Bianca arrives. She pulls a big bundle of coarse river reeds out of the back of her car.

Bianca shows us how to pass the reeds over the hot coals of the fire, to soften them.

“In the traditional sense, the smoke from the fire is making the reeds change their spirit” she explains. “From the point of view of science, what we are doing here is breaking dwn the cellular structure of the grass to make it more pliable.”

We all take bundles of reeds and cook them. It’s a delicate balance between making the grass soft but not burning it.

(Below: Bianca shows us how to soften the river reeds in the fire, to make them pliable.)

Once our reeds are softened, we head into the shed and sit on the floor to commence weaving.

“Tribal people used grass cord to make all kinds of things” Bianca explains. “Baskets, bags, fastenings for tools and weapons, all could be woven with these sort of fibres.”

She shows us how to twist the reed stems and wind them around each other to make lengths of strong, flexible string. The colour variation in the reeds gives the cord a pretty natural patterning, with speckles of brown, green, white, pink and even purple. I did a bit of knot tieing when I was a boy scout, so I catch on pretty quick. I make a couple of simple anklets, but some of the girls make elaborate, beautiful tiaras and necklaces, decorated with beads and feathers.

While we weave, Bianca tells us a story.

“My mum, Bev, and me, we’re very close now, but when I was a teenager, we didn’t have a good relationship at all. Mum has always been an activist. She has always been a proud and vocal Aboriginal woman, but when I was in my teens I was ashamed of who I was.

I grew up in a context that was profoundly racist. At school I was regularly abused and made to feel like I was an outsider. People called me names. They used language they knew would humiliate me. Words like coon, boong, Abo’, nigger. I was even spat on and physically threatened.

Mum always tried to reinforce my sense of self worth, to explain to me that I was not defined by what other people said, but as a teenage girl that positive message was overwhelmed by the scorn and cruelty of my peers.

I developed a lot of issues around alcohol abuse. I wasn’t attending school a lot of the time. I was trying to find a place where I was accepted. I was trying to do anything that would make me feel like I was someone else. I spent my time drinking, racing around in cars, and doing a lot of other self destructive behaviours.

When I was sixteen, I was in a very bad car accident. It was a head-on collision. My body was basically smashed. My arms and legs were crushed, and my head was extremely badly injured. The first doctors who looked at me thought I was a hopeless case, but I was very lucky because there was one doctor… one man, who made it his mission to put me back together…”

Her voice chokes off. She smudges tears out of her eyes.

The silence in the weaving circle is absolute. I can hear the rustle of the grass stems like a breeze on a field.

Bianca takes a slow breath. Her voice becomes steady and clear again.

“Nobody thought I would speak again, let alone walk, or live a normal life, but that one doctor, he never gave up on me. I really owe him my life. I remember the day, the first time I actually walked into his office on my own two feet. He got up, and came around the desk, and hugged me…”

All of us in the circle are crying now, and we have to put our weaving down to wipe our noses.

The scar curling Bianca’s lip seems more vivid now. I can now see a network of lines that trail across her legs and arms as well.

“While I was recovering, my mum was there for me every slow step of the way. The doctors healed my body, but it was mum who helped me put my mind and my life back together. I understood for the first time the direct way that the racism I grew up with shaped me. How it steered my life. I became determined never to bow to that sort of cruelty again. I wanted to work to create an Australia where young indigenous people didn’t have to experience what I went through.

I got very interested in the traditional culture of my people. I went to school again. I went to university. I connected with elders all over Australia, who still had knowledge of traditional practices, like the weaving we’re doing right now. I made it a mission of mine to keep those skills, those cultural traditions alive, and sharing them, in workshops like this, is one way I can do that.

Beverly, my Mum, she’s an inspiration to me. She has created this place, Mimburi. When we first walked this property, years ago, it was a mess. It was just weeds, and garbage, and totally neglected. This shed we’re in now was full of junk. You couldn’t walk in. We’ve made this place into a cultural resource. We want it to be a hub for the community. We want it to stand. We’re getting the message out to all the tribes. Come here. Be part of this place. We’re sending out message sticks, like in the old times. We are going to keep this place alive. The Banya Dreaming is going to happen again. The tribes will gather and unite here: black, white, everyone.”

Mimburi.

The music is done. The P.A. is packed up. People chat quietly around the fire.

Alex and I stand side by side on the deck of the old shed, looking out at the night sky.

In the valley below us, the tall, pale eucalyptus are still and cold as stone under the moon. A herd of white cattle steadily walk across the field.

“The moon is so beautiful tonight” I say. “Is it full now, or does it have a day to go, do you reckon?”

Alex looks up at the glowing sphere. He looks at me and smiles.

“It’s full enough for me, mate” he says.

>> Follow Raw Safari on Facebook and keep up with the latest posts.